When your church would like to gather as a public assembly to hear God’s Word, sing His praises, and receive Holy Communion, but your governor requires, under the color of a pandemic health emergency order, that everyone stay home—or perhaps permits a few at a time to gather, so long as they promise not to sing—what should you do?

The key to answering this question properly is the recognition that people are bound not to absolute civil obedience to an executive order, but rather to: (1) a constitutionally ordered civil obedience insofar as (2) such obedience does not involve any disobedience to God.

In a (perhaps surprisingly) harmonious manner, this answer rests simultaneously upon (1) principles of constitutional law and (2) doctrines of biblical theology.

An additional consideration, of course, is (3) Christian charity—love for one’s neighbor. While it may seem reasonable to expect that an urban mega-church with thousands in attendance poses epidemiological risks akin to a sports arena and hence it would be safer and more loving to suspend services (or at least to severely limit crowd size), the same level of concern does not apply to the more typical congregations of modest attendance, where declining membership already has resulted in a virtually automatic social distancing. Most churches today have fewer than 100 in attendance, although their architecture was originally designed to accommodate far more.

The present article focuses on that latter context: churches whose leaders may in good conscience choose to stay open even while remaining mindful of the pandemic—except that an executive order prohibits them from exercising their loving judgment or religious free exercise. In Idaho, the governor even went so far as to prevent clergy from making private visits to individual homes, i.e., the executive order allowed the pizza delivery man to come to the door, but forbade a pastor from bringing Holy Communion to a parishioner’s doorstep. When Caesar shuts down even the socially thinnest activities of religious free exercise while shoppers (despite posted regulations) routinely pass within six feet of each other, touching objects in common, then the newfangled proverbial argument “the church is dangerous to the community so it must be closed out of love for humanity” fails. The time has come, therefore, to remind Caesar that the First Amendment protects religious free exercise, yes, even in times of national emergency.

Rendering to Caesar and to God

“Render therefore to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” (Matthew 22:21)

With this brief statement Jesus suggested a double syllogism for defining civil obedience and divine worship, which in a fuller form goes something like this (adapted, with quotations, from Paul E. Kretzmann’s Popular Commentary of the Bible):

What to Render to Caesar

- All things that are Caesar’s are things that a person should render to Caesar.

- All things that are “mere temporal, earthly, things, which concern money, possessions, body, life” are things that are Caesar’s.

- Therefore, taxes, etc. are things that a person should render to Caesar.

What to Render to God

- All things that are God’s are things that a person should render to God.

- “All things which concern the Word of God, worship itself, faith, and conscience” are things that are God’s.

- Therefore, worship, etc. are things a person should render to God.

Thus we have the basic distinction between church and state, which Christianity introduced to Western civilization. Sometimes popes and bishops asserted undue influence over kings and princes, and sometimes kings and parliaments exerted undue influence over clergy and their parishioners. On balance, however, Christianity in general and the West in particular have been unique for their development of two distinct “kingdoms.” Henry VIII was the exception rather than the rule when he cajoled Parliament into establishing a state church and consolidating supreme power over both kingdoms—church and state—into an office held by one and the same individual, himself. As a corrective, America’s founding fathers distinguished church and state both constitutionally and theologically.

The Constitutional Issue: Rendering to Each American Caesar What Each Caesar Rightly May Claim

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution contains two important clauses in repudiation of England’s model of a state church:

1. The No Establishment Clause: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion … ”

2. The Free Exercise Clause: “ … or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

Meanwhile, the same Constitution contains in its preamble:

3. The General Welfare Clause: “We the people of the United States, in order to … promote the general welfare … do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

From the general welfare clause flows the separation of powers into three distinct branches of the federal government—Legislative, Executive, and Judicial—and also the separation between the federal and the state governments. The main point of this structure is explained in paragraph 2 of the Declaration of Independence: God has granted to each person inalienable rights to life, liberty, and property, and the purpose of government is to protect those rights. The founding fathers recognized the selfish and corrupt tendencies of human nature, and so they safeguarded the general welfare (that is, the protection of life, liberty, and property) in a diffused arrangement of checks and balances between distinct government offices (hence, the separation of powers and the layering of federal and state governments).

The federal-state relationship is further explained in Article VI of the U.S. Constitution, where we find:

4. The Supremacy Clause: “This Constitution, and the laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof; and all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby, anything in the Constitution or laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding.”

In an American context, therefore, “rendering to Caesar” occurs in a hierarchy of four levels:

- First, to the U.S. Constitution.

- Second, to federal laws and treaties.

- Third, to state constitutions.

- Fourth, to state laws.

Note that a governor’s executive order, which functions as a proxy for legislation during a state of emergency, is in fourth and last position. More specifically, an executive order is in fourth-and-a-half position, since state laws typically regulate the scope of executive authority during times of emergency. (For example, state statutes might allow a governor only 30 or perhaps 60 days of unilateral action, after which the legislature may extend or else terminate the governor’s emergency powers.)

Therefore, as a matter of law, an executive order stands or falls according to its conformity with or violation of the state’s laws, the state’s constitution, federal laws and treaties, and ultimately the federal constitution. More precisely, insofar as the governor touches upon a federal issue, all four levels of analysis apply; for purely local matters, only the state constitution and state law apply, as noted in the Tenth Amendment. Religious liberty (the focus of this discussion) is protected at both the federal and the state level, so all four levels apply.

It is the province of the judiciary to evaluate whether the governor’s orders pass muster at these four levels. (Several judges have issued temporary restraining orders—in North Carolina, in Kentucky against a governor, in Kentucky against a mayor, etc.—with regard to emergency orders that violated constitutionally protected rights. Indeed, one state’s supreme court voided an entire executive order for its failure to be promulgated according to the rule-making procedures dictated by state statute.)

It also is the duty of every office holder (from local police to lieutenant governor), having sworn an oath “to defend the U.S. Constitution from all enemies, foreign and domestic,” to refuse to enforce any unconstitutional orders issued by a governor. (Several sheriffs—in Michigan, in Illinois, in California, etc.—have stated their intention not to enforce several emergency orders that they deemed to violate their own oaths of office. Dr. Cordie Williams, a Marine veteran, similarly reminded the police of his oath and theirs, with the result that the police backed away from a crowd of First Amendment demonstrators in Sacramento.)

The Theological Issue: Rendering to God (Who Also Asks Us to Render Some Things to Caesar, But Not All Things)

Similarly, as a matter of theology, people are bound not to absolute civil obedience to an executive order, but rather to: (1) a constitutionally ordered civil obedience insofar as (2) such obedience does not involve any disobedience to God.

First, what does “constitutionally ordered civil obedience” mean?

The American republic derived its constitution in part from the British system, in part from early modern political philosophers (Locke concerning the protection of natural rights; Montesquieu concerning the separation of powers), and also in part from the Roman republic. Christianity emerged when the Roman republic had recently metamorphosed into an empire, but the notion that distinct offices have distinct powers as dictated by a constitution nonetheless remained operative to some degree at the time that the Apostles Paul and Peter wrote their epistles, now part of the New Testament. Both apostles alluded to the notion of “constitutionally ordered civil obedience.”

Paul wrote: “Let every soul be subject to the governing authorities. For there is no authority except from God, and the authorities that exist are appointed by God. Therefore whoever resists the authority resists the ordinance of God, and those who resist will bring judgment on themselves.” (Romans 13:1–2) Grammatically, “authorities” is plural: Paul recognized that more than one authority existed, each with a distinct office. As Paul continued: “Render therefore to all their due: taxes to whom taxes are due, customs to whom customs, fear to whom fear, honor to whom honor.” (Romans 13:7) Obversely, a citizen is not required to render taxes to whom taxes are not due, or customs to whom customs are not due; to each his due, yes; but to no one what is not his due but is someone else’s due instead.

Peter wrote similarly: “Therefore submit yourselves to every ordinance of man for the Lord’s sake, whether to the king as supreme, or to governors, as to those who are sent by him for the punishment of evildoers and for the praise of those who do good.” (1 Peter 2:13–14) An explanatory note in the Geneva Bible (an English translation favored among America’s founding fathers) explains that “ordinance” means “the framing and ordering of civil government,” in other words, the constitutional order. The phrases following “ordinance” sketch out the practical application of rendering to each mini-Caesar what belongs to that mini-Caesar: to the king, to the governors, etc. This same framework readily applies today to the four (and a half) levels in the Supremacy Clause that defines America’s constitutional order.

Peter concludes this section of his epistle with an echo of Christ’s distinction between God and Caesar, using a distinct verb for what properly belongs to each: “Fear God. Honor the king.” (1 Peter 2:17) Here we find also a hint of the next issue to be examined.

Second, when is civil disobedience warranted?

The same Peter who in his epistle encouraged obedience to the constitutional dictates of civil government, on two occasions personally refused to obey a human rule that violated God’s establishment of the church. When ordered “not to speak at all nor teach in the name of Jesus,” Peter replied with a pointed rhetorical question in mind: “Whether it is right in the sight of God to listen to you more than to God, you judge.” (Acts 4:18–19) When charged later with a violation of the Gospel-gag order (“Did we not strictly command you not to teach in this name?”), Peter replied, “We ought to obey God rather than men.” (Acts 5:28–29)

These examples, however, represent a last resort. The apostles sought, whenever possible, to honor every governing office, yes, even those of imperial Rome. Paul, for his part, exemplified how to work within the civil system, exercising his rights of citizenship. “And as they bound him with thongs, Paul said to the centurion who stood by, ‘Is it lawful for you to scourge a man who is a Roman, and uncondemned?’” (Acts 22:25) This plea spared him further bodily injury and gained him due process, as various magistrates intervened in his case by protecting his life and requiring that his accusers make a peaceful and public declaration of the charges against him. Ultimately, Paul exercised his right of appeal beyond the local authorities to the emperor himself. “For if I am an offender, or have committed anything deserving of death, I do not object to dying; but if there is nothing in these things of which these men accuse me, no one can deliver me to them. I appeal to Caesar.” (Acts 25:11)

We find here, in the earliest history of the Christian church, a lawful and respectful petition for redress of grievances: Paul’s appeal to Caesar. When Christian congregations today file lawsuits against governors and mayors, urging the courts to intervene for the protection of their First Amendment rights, those congregations fulfill their dual loyalties, rendering unto Caesar what is Caesar’s and unto God what is God’s. Let it be remembered that our Caesar’s Caesar is the Constitution, which includes, within the First Amendment, the following:

5. The Petition Clause: Congress shall make no law … abridging … the right of the people … to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

Applying Constitutional Law and Biblical Theology to Religious Liberty amid COVID-19

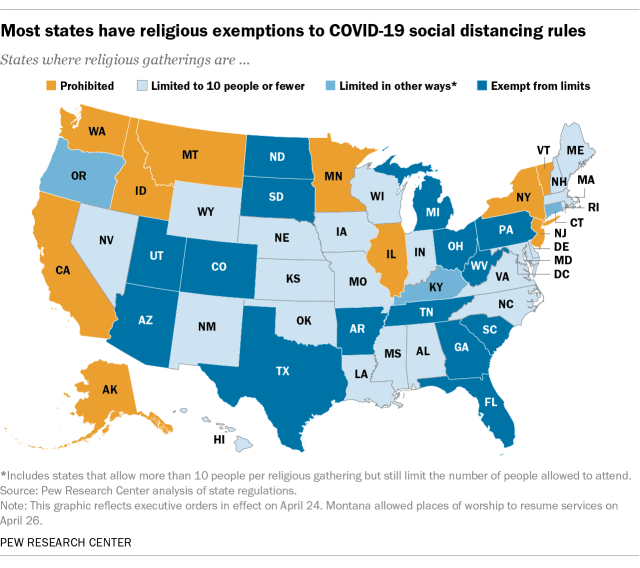

Not all coronavirus-era executive orders impinge upon religious liberty to the same degree, and some executive orders in fact protect religious liberty even while temporarily regulating social behavior in order to mitigate contagion. Judges, at both the state and federal level, have oaths of office to uphold as they impartially consider all matters of fact and of law in subservience to the Supremacy Clause. As we await their rulings, we reasonably may expect that some congregations have stronger cases than others, depending upon whether and to what extent the executive order infringed upon their fundamental rights of religious free exercise, assembly, and the like. All parties, however, ought to agree that every congregation has a right to petition and, having petitioned, a right to due process. All parties also ought to agree that the defendant (e.g., a state governor) has a right to respond in court to the complaint brought by the congregation. Fair is fair, for everyone involved.

Thankfully, the Free Exercise Clause and the No Establishment Clause of the First Amendment have generally been interpreted by the courts in a manner the enables Christians to live faithfully in accordance with the distinction made by Jesus and the Apostles between what belongs to Caesar and what belongs to God. As the U.S. attorney general recently emphasized, the U.S. Supreme Court has held that religious free exercise is a “fundamental right” and that any government agency that restricts that right has the burden to show that the regulation not only serves a “compelling state interest” but furthermore is the “least restrictive means” of doing so. That is to say, only in the rarest of circumstances do American courts tolerate a restriction upon religious free exercise. As a matter of constitutional law, religious free exercise is a fundamental right protected by the First Amendment; the six-foot rule, the ten-people rule, and other public health innovations must accommodate that right to the highest degree possible. Furthermore, the Fourteenth Amendment guarantees “equal protection,” a provision that would prevent governors from imposing stricter restrictions upon churches than upon other public venues, such as liquor stores (oddly enough labeled “essential businesses” and in many states suffering far less restriction than pastors and their congregations).

Happily, a legal complaint brought by some pastors against the governor of Idaho (remember? pizza delivery okay; Holy Communion forbidden) resulted in some telephone discussions between their lawyers (two of whom are my brothers) and the state attorney general’s office, after which the governor revised the executive order to accommodate churches. As one of the pastors said regarding a police chief involved in this case:

“I would like to clarify one thing with all concerned: Chief Fry went out of his way to be very helpful to me. He is a man of honor and a true public servant. I disagree with his conclusions, but in no way do I desire to portray him as an antagonist or adversary, nor do I blame him for the Governor’s order.”

In other words, petitioning for a redress of grievances can be quite an amicable affair—a truly civil matter in both process and result.

If, however, recourse to the courts fails to protect a congregation’s ability to fulfill its divinely established mission, then it behooves not only church leaders but also the lesser magistrates of the civil government and, eventually, individual citizens, to gauge the degree of tyranny and develop an appropriate response:

- Bear patiently in hopes that the governor will soon loosen the restriction?

- Appeal to a higher court?

- Interpose, if you hold an office of public trust and have sworn to defend the Constitution?

- Practice non-violent civil disobedience, in the spirit of the Prophet Daniel?

Even then, however, lawless rebellion shall not be entertained; rather, a measured response, in proportion to the four levels of injustice, will seek the good of church and state alike, in service to Caesar as much as possible, and in glory to God without fail.

Dr. Ryan C. MacPherson is the founding president of Into Your Hands LLC and the author of several books, including Rediscovering the American Republic (2 vols.) and Debating Evolution before Darwinism. He lives with his wife Marie and their homeschooled children in Casper, Wyoming, where he serves as Academic Dean at Luther Classical College. He previously taught American history, history of science, and bioethics at Bethany Lutheran College, 2003–2023 He also serves as President of the Hausvater Project, which mentors Christian parents. For more information, visit www.ryancmacpherson.com.